Oslo Architecture Triennale 2019

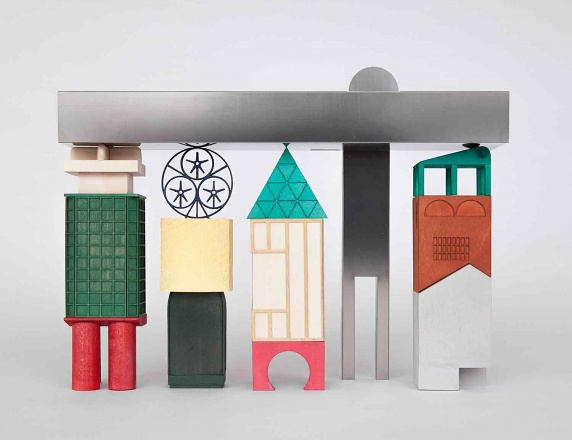

David Kohn Architects has contributed its research into the future of art spaces conducted over the past eleven years to the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2019. A model and essay form part of the Triennale 'Library' and will be on show at the Nasjonalmuseet – Arkitektur at Bankplassen 3, Oslo, between 26 September and 24 November 2019.

In 2008, structural engineer Jane Wernick (HRW) and environmental engineer Colin Darlington (Max Fordham LLP) collaborated with David Kohn Architects on a winning submission in the Arts Council England competition to conceive of an 'Arts Space of the Future'. The proposal can be seen on David Kohn Architect's website here.

The Art Council's brief asked for designers to consider climate change and sustainability, changing future lifestyles, new and developing arts practices, expectations and forms of participation, and the move towards more flexible, publicly engaged buildings. David Kohn Architect's response was a carbon neutral art garden in the Thames Valley entitled 'Heterotopia' after Michel Foucault's coinage in his seminal essay 'Of Other Spaces.'

Willow coppicing would be planted across a network of existing parks in East London that are adjacent to areas of extensive house building. The coppice would fuel a carbon neutral power station that would in turn run installations, events and venues that would crop up in the circles of felled coppice. Participation and production of art was prioritised over reception and consumption and the power station functioned like Tate Modern as though the turbines had never stopped.

In the summer of 2019, David Kohn Architects invited the team from 2008 to revisit the Heterotopia project in the context of the OAT 2019 theme 'Enough: The Architecture of Degrowth.' Despite there being many overlaps between the concerns of the Arts Council England 2008 brief and the OAT 2019 theme, would the team pursue the same responses? Has the environmental and cultural context changed such that the scheme would be even more timely, and in fact the hotly anticipated future has arrived, or would Heterotopia be invalidated?

Jane Wernick was joined by environmental engineer Nick Cramp (Max Fordhahm LLP), artist Pablo Bronstein and graphic designer Mark El-khatib. The discussion was recorded and the transcription follows.

PB Pablo Bronstein, artist

NC Nick Cramp, environmental engineer, Max Fordham

MEK Mark El-khatib, graphic designer

DK David Kohn, director, David Kohn Architects

BM Bushra Mohamed, architectural assistant, David Kohn Architects

JW Jane Wernick, structural engineer, engineersHRW

JW My overriding occupation is different now, because of the urgency of climate change. If we were to be really radical as a society, we would only build new buildings if it were absolutely essential. We would also not allow any spaces, especially housing, to be used as assests for investment purposes. We should put all of our energies into modifying our environment in ways that make it adaptable for future lifestyles. Ideally we could aim for zero growth.

As a structural engineer our role was always to try an understand the brief as well as possible, then come up with ideas and solutions that best fitted the brief. Now, we have to bear in mind much more stringently our industry’s impact on the planet. And we now know a decrease in growth has a positive impact on the planet.

NC There are a few lessons we can learn now from looking at the Heterotopia concept, and one is that it shows us how early our investigations into a less damaging economy were. The sun is our primary source of renewable energy; we should be using that more – rather than biomass fuels, which we proposed at the time.

JW We could do this by not proposing a new building on a greenfield site but instead repurposing buildings right in the heart of London.

BM In relation to art spaces, do we feel that The Arts Space of the Future is still that key space that will host artworks?

PBThe structure of the art world that we recognise at the moment can only do so much in terms of degrowth. It has moved away from the idea of highly worked, individually made objects and into a world of editions and reproducible artworks. For example, the ideal artwork is something that when you walk into a room you see a work on the wall and you are able to say, ‘Oh, that is a spot painting by Damien Hirst. There are only 18 of these in existence and 17 of them are already in museums’. That is when you know you have a really important artwork. The problem with the world of editions is that it creates a lot of waste and often does not use environmentally friendly materials. The amount of air miles and waste produced just to sell an edition of an artwork is extraordinary.

In the long term, if an object has been very carefully made and there is only one of them, then humans historically tend to look after them better than objects that are produced in larger numbers. It is a question of whether the institutional museum of the future is able to radically detach itself from the workings of the international art market.

MEK In order to engage a local community who would probably be alienated by the kind of art that Pablo is talking about, which is so divorced from their reality, you would need to look at other models. Plenty already exist, such as Grizedale Arts, run from a more rural location; artist-run Eastside Projects; and MIMA [Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art] – framed as a ‘useful museum’ for the community. Somehow, this is also addressing two forms of art practice. Should architecture lead, or follow, art practices of the future?

JW There are parallels in music. We now have music that is produced by machines, and yet we still desire to see a human being play the violin brilliantly. These types of musical experience can exist in parallel.

BM What is the driving force behind the application of degrowth?

JW Do we as a society have to ditch the idea of capitalism?

PB It is important to separate the difference between the conceptual importance of art within a commercial world, and art that is functioning solely with the aim of making money. It is very difficult to identify truly interesting machine-made art.

NC One of the primary functions of an art gallery is to conserve precious objects, but still in every gallery works are constantly but slowly being damaged by heat, humidity and light. In fact artworks have a finite life, so a more sustainable, but very radical, approach could be to acknowledge this and to declare it, thus allowing the works to degrade back into the earth and consequently removing some of their value as an asset and the need to keep them in such energy-intensive buildings.

PB I think that makes sense from a point of view of socially minded art, so in other words, if the artwork is about something that is created and experienced by people who make it and the local community, I can understand the need to not preserve that beyond its lifespan. However, If you are dealing with a historically important artefact that has large cultural value – to give a polemic example: an artifact fromPolynesia that is worshipped in Polynesia – we understand it as an impressive, useful object that people in another part of the world worship. We would want tohopefully preserve that the best we possibly can for future generations.

It would be inconceivable to build into a museum an acknowledgment that the objects are going to come off worse by being in there than by being somewhere else, because there is always going to be a museum that says: bring your rare 16th-century tapestry and you will still be able to see it in 100 years’ time.

DK There are a lot of large gallery spaces in big cities that are effectively built to support the market, and we have identified that these spaces have a significant commercial role in the art world.

The conversation seems to be suggesting that one could almost cleave all that. In that case, is there another physical space that we might all be involved in creating or advocating?

If I think of a spatial analogy for what you are describing, one option is a highly atomised gallery in which the scale of importance of an institution like the Tate can only be matched by 100 tiny spaces scattered through a city.

MEK Thats like a biennale model? A curated programming of events and exhibitions happening in many locations across a city.

PB I think we can all agree that museums have become too big. Tate Modern in its recent enlargement has taken a step too far in terms of what can be done comfortably in a day. On the other hand, I think at a smaller scale, a museum will also struggle to generate peripheral interest. It has to offer at least one or two hours of something interesting.

DK The comments about limiting the life of an artwork, that a structural engineer will not be building structures, and this question of unique handmade artworks offer a future outside of an inflated marketplace. All these things together are very provocative. The hope is that what we are sharing here is our purpose in architecture, and we may all take something from it in a future project. Our reflections show how we have moved a long way from our original proposal.

However, I am still intrigued by this group of people’s abilities to make spaces and effect change. I wonder: if there are these spaces, what might they be? And what will our role be? What are our jobs?

JW If we did have a society where everyone was paid a basic income, then artists could survive, and we could have a sensible amount of good art being made by all sorts of people, as opposed to just a few superstars. That would make it much more accessible.

BM Perhaps we would think of collaborative ways of doing our current jobs based on what is needed rather than pigeonholing our skills.

NC Jane and I stand in very different positions because the first function of structural engineering is to keep buildings from falling down. Structural engineering has been extremely successful at this and if the building stock is not at risk of structural collapse, we can reuse it, whereas most existing electrical and mechanical systems are unsuccessful at delivering the reductions in emissions we need, so we will have to replace a great deal in order for us to meet the date we have set for a zero-carbon economy.

JW We don’t know how to make zero-carbon structures either.

NC But we have an idea at least, which is not to make any more buildings but to reuse the structures that we have got and change their fabric. In that sense the architecture of the past is unsuccessful as well, in that it is not keeping enough heat in or heat out. We will need to effect big changes in the existing building stock in order to align ourselves with the necessary aspiration of zero carbon.

JW I think we should be using this as an opportunity to improve the building stock. Lacaton & Vassal has done a fantastic scheme in Bordeaux. It is a housing block to which they have added winter gardens along its sides, whilst people were still living there. It is quite fantastic. It provided insulation with the buffer zone and also made more social spaces, because the residents speak to their neighbours along these strips. I think we should be taking this zero-carbon challenge as a real opportunity to improve our social spaces.

NC It is interesting, even though it is discussed more and more, largely what we see written in the architectural press is about new buildings. There is not a huge push within the industry to take what we have already got in this city and beyond, and turn it all into something that works.

JW And it is hard to turn those projects down because you need the work, and clients think they want shiny new buildings and you go along with it.

DK The same time we entered the original competition for Arts Council England [The Arts Space for the Future], we promoted an idea called jujitsu urbanism, which was taking the existing energy in a city and redeploying it within the same physical forms, buildings and spaces, and reorganising uses into new configurations.

If you need different art spaces in the future, does it matter that they are accommodated in a different building typology? Does reuse of existing buildings mean that the supposed match between use and building form becomes less important? For instance, if you are building a new gallery you will need to get certain proportions right, make sure the air supply is hidden, allow for certain kinds of daylighting – and I suppose within London there is a sufficient variety of building types for you to find the best option, but presumably it is no longer going to be a tailored solution.

JW It would be much easier for an art space than for a performance space, where acoustics and sightlines are so critical. For example, you could imagine turning this office building into an art gallery much more easily than, say an opera house.

NC But, there is not so much variation in building systems. Realistically, in the wintertime almost everywhere needs to be heated up and in the summer time wants to be cooled down. There is great deal of variation in spatial terms but in functional terms most internal spaces work in a similar way: lights on at night, a certain allowance for daylight, a certain demand for heat.

Freeing exhibitors from the onerous loan agreements and conservation requirements that Pablo mentioned would help us advance. For example, some large institutions such as the Tate have revised their approach to conservation in recent years to be more flexible.

Galleries can now have carefully varying light and humidity levels, for example. You have to understand the implications of that and accept it or not. It is a different approach to the inflexible stipulations of the past; this kind of progress needs to be led by govenments, institutions, galleries and collectors powerful enough to propose what individuals cannot.

Redefining expectations could do a great deal to address the climate emergency – it applies to us as people, too. Accepting, for instance, that it is very warm in the summer and coping with that. I think it has to come from architecture and the construction industry, too. It is about asking: how can we use what we’ve already got in a completely new way? A kind of degrowth of expectation.

DK What I am aware of is that this conversation has reminded me of a lot of historic conversations that touched on similar things. It makes you realise that although we may not be promoting doing a building like Heterotopia 2008 anymore, we are in a moment where the industry is going to change and practices will have to change, too.

JW There are two drivers that are real: there is the fact that it is now law that we have to get to zero carbon by 2050. You can argue with the definition of zero carbon because it does not include all the imported carbon. Secondly, we are post-Grenfell and that is definitely going to change the way we work. These facts, combined with the work of Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg are quite exciting. I am optimistic that we are going to make changes. Whether we will be fast enough remains to be seen.

BM And in a way, it needs to happen within all disciplines.

JW Yes, it has got to include lawyers, employers, insurers, economists, all those

other disciplines.

MEK …and artists!

NW Agriculture, transport and energy providers are going to have to lead the way because the onus is on them rather than individuals.

JW A lot of it is also from the financers. The EU are now saying they are not going to give loans to any more petrochem projects, which is very good. There are changes being made politically and that is what we need.

PB There are a couple of things I would like to conclude on. The role of tastemakers in society remains very important. You can shame people into changing their behaviour quite easily. For example, there has been no new information about the fur industry in the last 100 years, and yet in the 1930s people wore fur coats and now it would be shockingly unacceptable for somebody to wear a fur coat in public. And that is mostly the result of 200 very angry fur campaigners and a couple of names in the media, which has had a huge impact.

The role of taste and fashion have a big impact in art. If a certain artist, famed for their reproductions and editions, was instead associated with environmental disaster due to the waste produced, we would not be showing their work anymore.

Institutions such as the Tate are extraordinarily aware of what people are saying on the street. Within 25 angry tweets about the carbon footprint of a Jeff Koons show, the Tate would think twice about their future exhibitions.

A more sustainable model is to focus on making objects that are the best example of their time (which is what very handmade objects frequently are). This involves all disciplines. If we wanted to live in a world where people very lovingly produced objects, we would have to have buildings that were also designed and constructed in a very loving way, incorporating very loving details. We would have to understand buildings, clothes, food, furniture, etc in a very handmade way again.

I do not know if the current climate of producing very slick objects is pointing us in that direction.

BM I think that is a good point to conclude on: make a few things well rather than many things faster and cheaper.

Conversation took place on 1 August 2019 at David Kohn Architects, London.