2008/09 A Contemporary Theatre

Dalston began to grow in earnest with the arrival of the North London Railway’s City Extension in 1865. The small village was transformed into a thriving city quarter characterised by a tight grain of varied property ownership along its major axis, Kingsland High Street, that has ensured a constantly changing streetscape. The arrival of the East London Line station at the southern end of the High Street in 2010 will again bring about significant change. 500 new flats, public facilities and a new public space, Dalston Square, will shift Dalston’s centre of gravity, alter the scale and grain of property ownership and establish a new economic paradigm that will challenge that of the surrounding 19th century urban fabric.

For old Dalston, both the urban fabric and its inhabitants, a current challenge is to understand the relationship between the existing urban fabric and its institutions, so as to better steer changes to wider advantage. This raises questions, such as to what extent has Dalston’s architecture affected the character of its institutions? As the scale and grain of the city changes, what effect will this have on the day-to-day practices of those who live and work there?

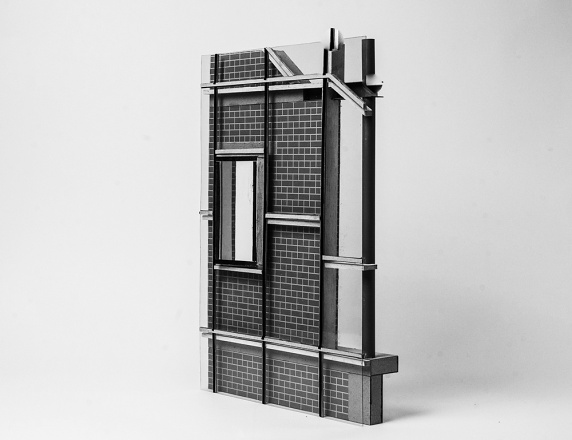

These questions are exemplified by the plight of the Arcola Theatre. The Arcola grew out of a local Turkish theatre project started in 2000 and is housed in a 19th century warehouse on a backstreet some distance from the transport and social centre of Dalston. Its modest beginnings were matched by its setting and its theatre spaces were no more than warehouse floors. Columns regularly appear on stage, there is no room for flying sets yet the theatre is widely regarded as one of the most exciting venues in London. Nonetheless, like other local institutions, the Arcola is now under pressure to relocate due to the future value of its warehouse as housing. Given the success of the theatre and its importance locally, the new sites being considered are in a much more prominent location than Arcola Street — across the road from the new Dalston Square.

The last great period of theatre building coincided with the arrival of railways in central London at the end of the 19th century which allowed suburbanites to satisfy their burgeoning taste for music halls and theatre. Many of the conventions of theatre architecture, the grand facades, elaborate foyers and proscenium arches, were established during a building spree that saw more than 200 theatres built in 25 years. Through these conventions, theatre architecture attempted to achieve a kind of meta-architectural language by both expressing its civic purpose as a significant cultural gathering place while at the same time imparting a sense of the nature of theatre as self-reflexive communication.

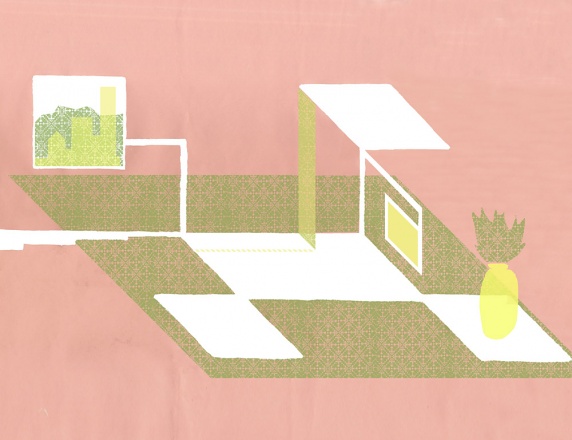

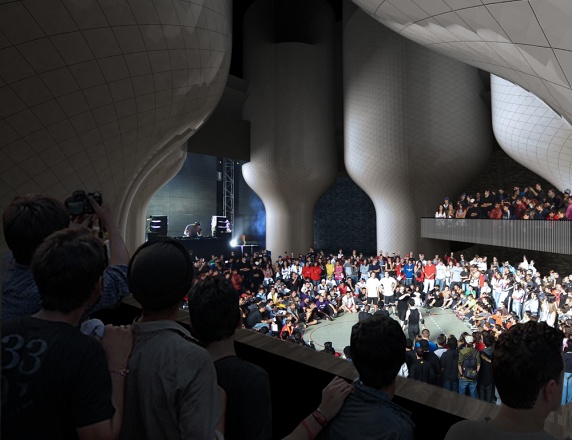

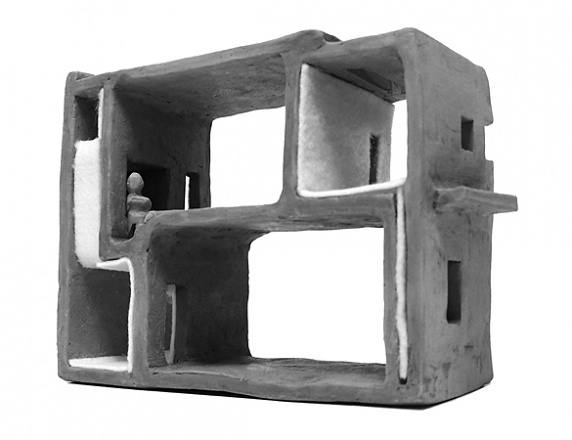

The potency of theatre in a warehouse can be seen in this context of architectural conventions and layered meanings. The Arcola warehouse becomes a hidden theatre, a provisional theatre, a raw, essential, architecture stripped of ornament, as though the space in which theatre takes place has expanded from the stage to the whole building, pushing at the envelope of the city beyond. The implications, therefore, of the Arcola moving from its backstreet location to a prominent site beside a major development requiring a new building is highly problematic, but a rich field of investigation. To what extent should the architectural language of the new building articulate resistance to gentrification? How does the scale of a theatre condition the choice of an appropriate architectural language?

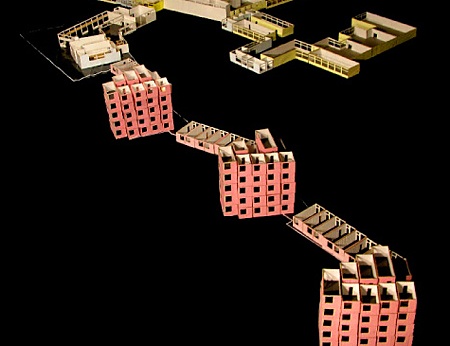

In this context the eighteen students of Diploma Unit 5 developed proposals for a new Arcola. Whilst difference in approach was encouraged and as a consequence the schemes present an array of possibilities, nonetheless certain themes emerged: The many-faced theatre addressing different Dalstons; the theatre as a picturesque topography co-opting surrounding urban and natural landscapes; hidden architecture, or new architecture camouflaged as existing; the progression from the familiarity of the street to the other-worldliness of the theatre interior; the decorum of the interior architecture and its relationship to both character and flexibility.

At the beginning of the year, the unit set out to map the historical relationship between theatre buildings, theatre practice and audiences, and the role theatres play in cities culminating in an attitude towards found space theatres such as the Arcola. Our research involved watching performances, group surveys of six London theatres from the last 150 years and visits to theatres in Milan and Vicenza. Workshops were held with theatre directors, set designers, acousticians and theatre scholars. In the following pages the students’ eighteen propositions are set out interleaved with essays kindly contributed by several of the unit’s visiting critics. Collectively the work hopes to contribute to debate surrounding theatre architecture in a changing city.

Students:

Yougesh Bhanote, Katarina Bjorling, Stephen Chown, Caterina Da Via, Georgina Fall, Richard Gatti, Haakon Gittins, Stephen Hogan, Nisha Kurian, Nick Maari, Sam McNeil, Charlotte Mockridge, Adonis Papakirykos, Ummar Rashid, Keigo Shinada, Aleksandra Tarlowska, Michael Tze Wei Na, Crystal Whitaker.

Tutors:

David Kohn, Silvia Ullmayer

Consultants:

Stuart Colam, Arup Acoustics, Graeme Flint, Arup Fire, Paul Burgess and Simon Daw, Steve Baker, Alan Baxter Associates, Michael McKinnine, QMUL, Ben Todd, Arcola

Critics:

Peter Carl, Liza Fior, Tim Foster, David Gothard, Eddie Heathcote, Robert Mull, Tim Ronalds.

Graphic Design Consultant:

Practise

Thanks to:

Caruso St John Architects, Franco Laera, Grafton Architects, Piccolo Teatro, La Scala, Teatro Franco Parenti

More Teaching Projects

Future of Collaboration

Future of Collaboration Porto Academy 2022

Porto Academy 2022 2019/20 AA Diploma

2019/20 AA Diploma 2012/13 Constructor Course

2012/13 Constructor Course 2010/11 Art/House/Power

2010/11 Art/House/Power 2014/15 City Details

2014/15 City Details 2009/10 Worlds Within Worlds

2009/10 Worlds Within Worlds 2007/08 Social Gravity

2007/08 Social Gravity 2006/07 Play for Today

2006/07 Play for Today 2006/07 Interaction of Architecture

2006/07 Interaction of Architecture 2019 Girona Masters Workshop

2019 Girona Masters Workshop 2020/21 AA Diploma

2020/21 AA Diploma 2021/22 The Future of Collaboration

2021/22 The Future of Collaboration