Published in Building Design, Issue 1878, July 2009

Valerio Olgiati’s exhibition is the Swiss architect’s first in the UK. Part of a larger show originally at ETH Zurich in 2008, the present version comprises seven exquisite white models accompanied by a low table displaying reference images on two digital screens and a new monograph.

For those familiar with Olgiati’s work, the delivery is reassuringly in character — almost the only exhibition interpretation is a sign informing you of the scale of the exhibits, “Models 1:33, Drawings 1:66”. (An earlier Olgiati monograph was entitled “Plan 1:100”.) The models are presented much like a sculpture installation: abstract figures on slender steel legs, carefully arranged and scaled to the room, a perceptible serial development from one piece to the next, a relative lack of interpretative distraction. In fact, the RIBA Gallery rarely looks this refined.

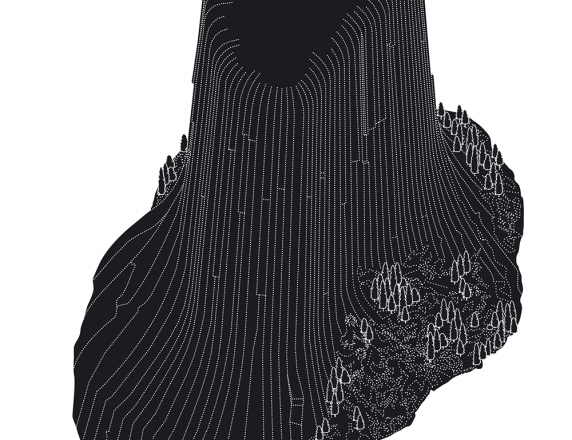

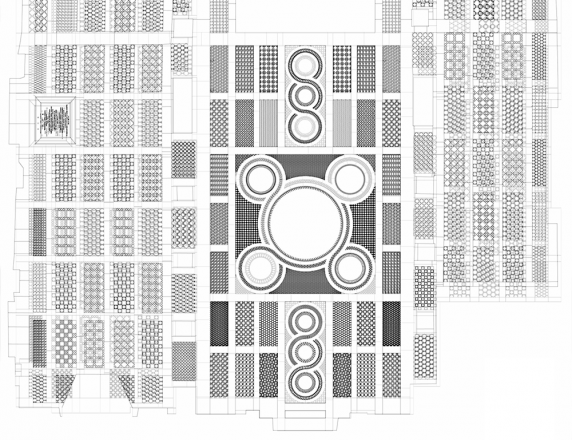

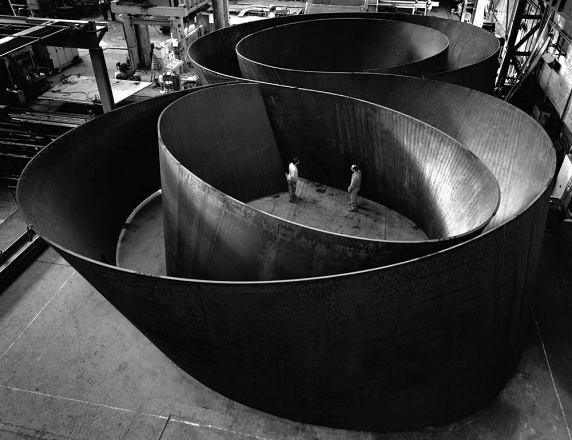

At a sculptural level each model suggests an exploration of the nature of dense bodies, their formal compactness, gravity and sense of centrifugal rotation. The smaller pieces are comprised of geometric frames floating above inflected structural armatures; in the larger pieces the outer forms themselves are rotating or staggered as though turned on a lathe. Beyond these consistencies, each model shows the principal idea governing the conception of a building project.

As the exhibition notes insist, Olgiati intends his models to be interpreted in the context of his “Iconographic Autobiography”, a collection of images displayed on screens in the centre of the room. Ranging from Fathepur Sikri to Borthwick Castle, from Shinohara to Rossi, the architectural wonders on display represent Olgiati’s memory bank of ur-forms. The dialogue between the models and the images constitutes Olgiati’s claim for a complete architecture of mythic provenance, removed from the specific contingencies of time and place.

Although the models in the show make no distinction between built and unbuilt projects, the majority are in fact complete. At the level of architectural parti, each building harbours an enigma: the labyrinthine central stairs of the Zernez Visitors’ Centre (2008); the crank in the central column under the roof of the Gelbe Haus (1999). In terms of their architectural order, the projects are uncannily pitched somewhere between laconic post-war modernism (with traces of early OMA) and Mayan archaeology. You get the impression of having seen them before without quite being able to remember when, which results in a mixture of delight and disquiet.

In the smaller projects (Yellow House, Paspels, Bardill House, Olgiati studio), these discordant touches are beguiling, providing a welcome antidote to iconic architectures that present a single incontestable image. The buildings’ quite staggering constructional precision only serves to heighten one’s appreciation. At the larger scale, however, the same strangeness seems more problematic, as the enigma previously hidden from view comes to dominate the primary architectural order. In the competition-winning scheme for the Perm Museum XXI (2008), for example, the size of the building, the scalelessness of the curtain-like order, and the symmetry and singularity of the form suggest a greater struggle to relate the architecture to its possible inhabitation and consequently its wider signification. This raises the question of whether the singular approach Olgiati promotes across the projects is appropriate to larger or urban propositions.

The extraordinary influence of Swiss architecture over the past 15 years has helped reintroduce into Britain concerns for the relationship of academia to practice, construction to expression, and invention to tradition. Nonetheless, the work of Swiss practices has been diverse and inevitably not as singular as the brand suggests — think of Herzog & de Meuron, Peter Zumthor and Peter Märkli for example.

In this context, Olgiati’s work reasserts certain tenets and rejects others. Arguably, it shares the motivation present at the outset of each of these practices to produce architecture resistant to market commodification. Where Olgiati’s work diverges is in turning to a mythic, rather than an artistic or vernacular, basis to this resistance. On the one hand this approach affirms imagination as a stronghold against the instrumental logic of late capitalism. On the other, it raises the question of the possible disconnection with the everyday world that such a stronghold might create. Either way, the precision and invention on display is able to bring such contradictions clearly to one’s attention and will undoubtedly inspire debate and fresh initiatives.