Published in the Tutti a Tavola Exhibition Catalogue, April 2010, pp. 154-159

What makes a successful café or restaurant? The answer must be long and touch on a multitude of subjects and roles: The location, the owner, the owner’s friends, the food, its price, the chef, the licensing laws, the marketing strategy, the com- fort of the interior. Amongst this broad field of influences, only a few, starting with the interior, are touched by designers, and not every café or restaurant has involved an interior designer in its making. Even fewer will have involved an architect and it is this question of what contribution an architect may bring to design that I would like to address. A lunchtime meeting, an afternoon spent reading over coffee, an evening party, are remembered because of the pleasure of the social occasion. The conversations that took place, possibly with strangers, the thoughts that grew, the celebration that was realised. For each of these situations and pleasures there are physical conditions that allow them to take place. We all remember the restaurant in which everyone had to shout to be heard and the gradual resulting onset of aural exhaustion. We also remember the large gathering of friends in which conversation bounced around the table and the pleasure of company deepened as the evening wore on. The Austrian architect Hermann Czech, in his essay, Cafés (in Christophe Grafe, and Franziska Bollery, eds., Cafés and Bars, Routledge, London 2007) proposes that “A café is not to be noticed, but remembered”. In the sometimes harsh economic context of contemporary cities, where new cafés, bars and restaurants come and go like the wind, his statement is provocative. One common response to this context is to make an impact, provide an iconic image of social life that sears itself across the retina and assures easy marketing, and hyperbolic word-of-mouth notoriety. Such a design response is primarily directed at branding or theming, it is concerned with the consumption of the restaurant event rather than the production of it. Czech’s provocation therefore, is to rather focus on the production of those spaces that allow conviviality. How can cafés, bars and restaurants be made in such a way as to provide conviviality the best context in which to flourish? The conditions necessary for an enjoyable conversation in a room surrounded by others doing the same are simple, but essential. In his essay, Czech asks how far apart are the tables? How far apart are the chairs? Does one feel claustrophic? Is there a view to provide a contrast to your intimacy? Is there a mirror that allows one’s eye to relax momentarily? Yet more considerations: what are the acoustic properties of the materials surrounding the table and the proportions of the room? Can one see all of the other diners? Can one see the kitchen, talk to the barman, move to the bathroom without squeezing between diners and tripping over unsuitable chairs? Instead of the modernist adage, “form follows function”, acceptance of these preconditions for conviviality means reversing the formula, so that function follows form. Rather than the image of a wonderful evening with friends talking over dinner being the design driver, it is the careful and deliberate construction of the conditions for the event that will allow it to happen.

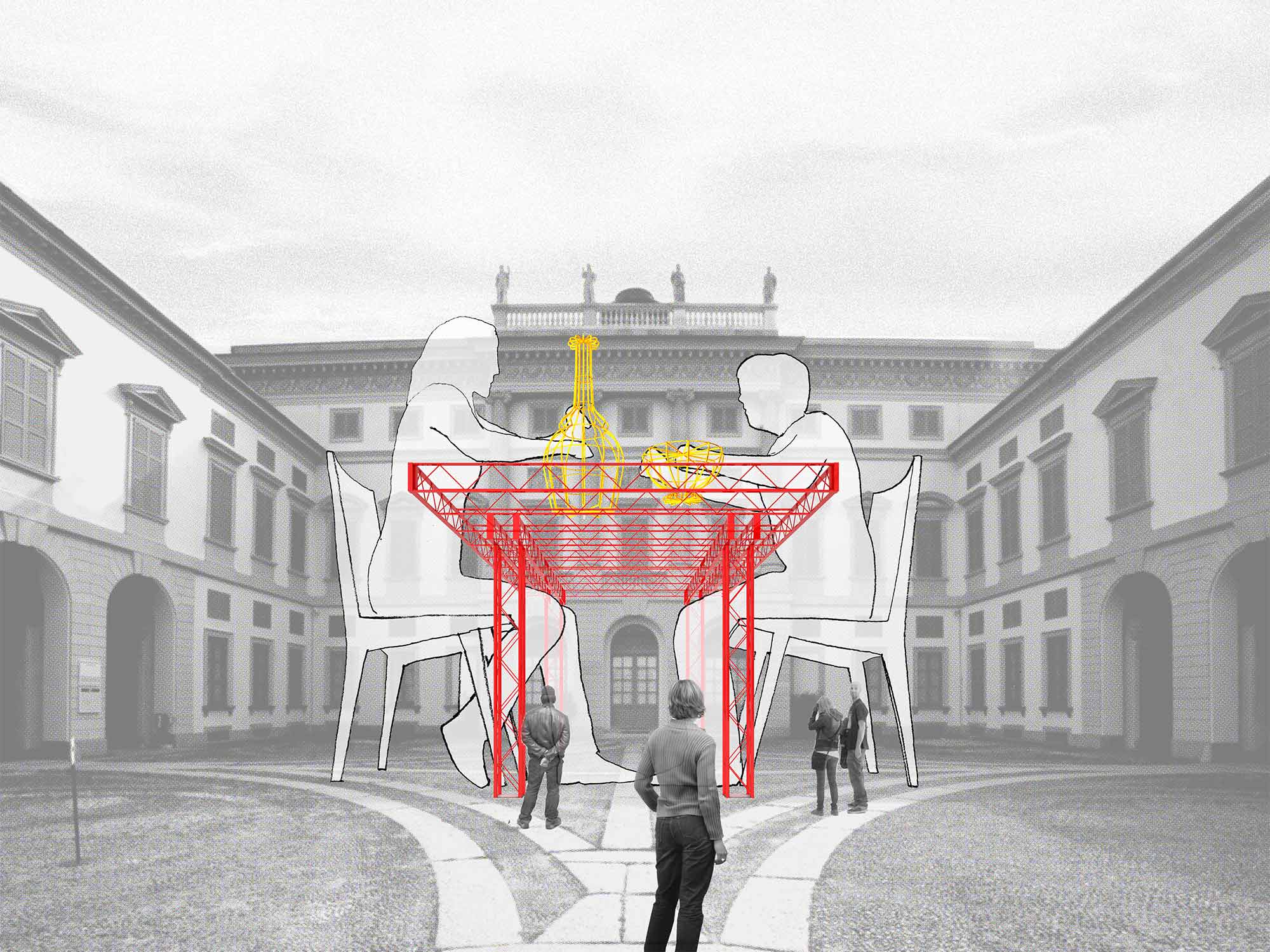

Being liberated from pursuing an image, one is then freed to construct new forms of conviviality through the orchestration of all the senses. There are key examples of interiors where their architecture has played a memorable part. The American Bar in Vienna, designed by Adolf Loos in 1908, has a diminutive 5 x 4.5 m interior that, nonetheless feels spacious. At low level are rich, leather banquettes surrounded by mahogany panelling with a bar adjacent running the length of the room. Above head height, however, the walls are mirrored on three sides. In front of the mirrors are half and quarter timber columns which when reflected appear as a vast colonnaded canopy standing over the evenings intimate proceedings. The Wolseley Restaurant in London, designed by David Collins in 2003, has a palpable sense of theatre brought about by the arrangement of interior screens and fixed seating at high and low levels. A refurbishment of a grand showroom built for Wolseley cars in the twenties, the room revolves around a central star in the stone floor where one presumes once stood the flag- ship Wolseley car of its day. Now it is occupied by the most desirable table in the house, encircled by a horseshoe of banquettes and framed by smaller glazed dining rooms. A more democratic, but no less theatrical arrangement was once to be found in Achille Castiglioni’s beautiful, but sadly demolished, Splügen Bräu Beer House-Restaurant on Corso Europa in Milan. Designed in 1960, the seating was arranged in rows of banquettes at different levels that both provided intimacy and cross-views of other animated diners. All under a familiar blanket of Castiglioni bespoke hanging lamps. In 2008, my studio David Kohn Architects was asked by the London restaurant Bistrotheque to collaborate on a “pop-up” temporary restaurant at the Royal Academy of Arts. Pop-ups, from shops to clubs, have gained in popularity over recent years and arguably represent the sharp end of brand-lead quick cultural fixes. Despite the fact that the restaurant was only to be open for three months, we were nonetheless as faithful as possible to the idea of a carefully constructed comfort. The site was an awkwardly proportioned gallery space at the back of the Royal Academy with an extraordinary view of a large brick wall. Within this space we installed a new room made of timber art-packing crates. The thick wall served to tighten the room’s proportions to be more vertically elegant and to create a back-of-house around the edge of the gallery. The wall cut back into the space to create new corners and introduce a variety of scales into the interior. At low level, the panelled walls alternated between doors allowing waiting staff into the room and recesses filled with mirror. The effect of the range of scales, from recess, to corner to wall to reflection to window to room, created both a sense of intimacy and of grandeur that was mediated by the architecture. Each of these examples shares a sense of the theatrical. However, it is important to distinguish two different ideas of theatricality if the term is to be useful in contributing to a debate about design. On the one hand, theatre is commonly understood as a spectacle seen at a distance where the audience and actors are separated and the artifice created by scenography is primarily visual. This is most evident in the proscenium arches that flourished in nineteenth century theatre design which is how most twentieth century audiences have encountered theatre productions. Such a form of theatricality has parallels with the iconic image making that can accompany design I described earlier. The second idea of theatre is that of the city ritual in which citizens gather to affirm their social bonds in public spaces through performance. Here the city is the context, the audience are actors and the experience is haptic, involving all of the senses in the manner of Venetian carnivals. Understanding the city as theatre can be the architect’s gift to the design of spaces for convivial gathering. In such a city, each physical change can help play its part in providing a context for pleasurable use.