Published in MADE: Materials Architecture Design Environment, Journal of the Welsh School of Architecture, Issue 5, September 2009.

The academic Peter Carl, in a recent article about the work of David Kohn Architects, described our approach to the city as a ‘species of architectural jujitsu, whereby subtle interventions activate the rich thematics and history of a site’. Enjoying the analogy, I have taken the opportunity to expand upon its possible implications for a contemporary urban practice.

Martial arts employ two groups of techniques, the hard and the soft. Hard techniques involve striking an opponent head-on with maximum force and are improved by physical strength and conditioning. Hard responses to hard attacks involve blocks and diagonal cuts across the path of the oncoming assault. Soft techniques, on the other hand, are concerned with harnessing and redirecting the energy of an opponent to both disarm and attack and require flexibility and skill. Jujitsu, amongst all of the martial arts, elevates softness (Ju) to the level of an art (Jitsu).

For its adherents, Jujitsu is seen as superior to all hard techniques because of a familiar philosophical inversion – the greatest hardness can only be achieved through its opposite. “The word flexible never means weakness but something more akin to adaptability and open-mindedness. Gentleness always overcomes strength.” Rather than an expectation of ever increasing levels of energy to overcome a given situation, Jujitsu requires a willingness to redirect energy and to therefore invent a response that will fit the form of the attack.

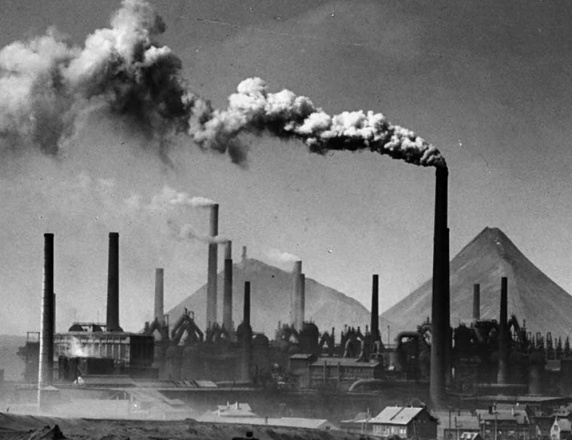

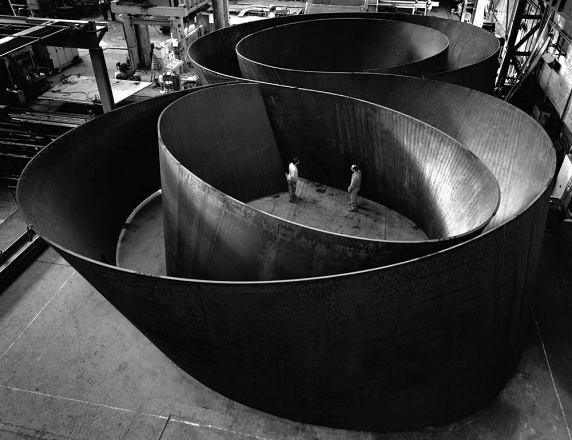

In a 21st century mature city like London, urbanity is the existing condition. Vast amounts of energy have been expended over centuries to create the dense structures in which the city’s inhabitants go about their daily business. In this context, 19th century railway lines represent an extreme of hard technique. Cutting across streets, squares, parks and rivers they achieve their goal with brutal muscularity. The problem of mass access into the hearts of dense populations was realised with a violence that 150 years on, there is neither the political nor the economic appetite to match.

Jujitsu Urbanism might describe a 21st century approach to contending with the potential energy of the contemporary city. Rather than meeting problems of migration, densification, contraction, transportation and poverty with the kinetic energy of wrecking balls, piling, formwork and heavy lifting, an art of gentle energy redeployment could be adopted. The strength of the Jujitsu analogy lies precisely in its violent origins. Too often in urban debates any notion of subtlety, flexibility, or adaptability of technique, is perceived as ultimately weak, confirmation of the Victorians’ greatness alongside our relative lack of backbone, and ultimately an acquiescence to the inevitable decline of cities. Jujitsu Urbanism on the other hand, having been informed by centuries of Samurai warriors, is battle- proven to defeat head-on onslaughts.

Principle of Leverage

In April 2008 our practice completed its first built project, a new gallery for Stuart Shave Modern Art. The site was the ground floor of a 1950’s office building - six stories tall, concrete frame, brick infill, strip windows - an essay in utilitarian and anonymous post-war construction. The pleasures of the architecture were however limited to a contemplation of the structure’s rigorous economy and simple plan. In contrast, the ground floor street frontage could only be described as mean. The wide brick-clad columns of the upper floors resolved themselves in narrow concrete posts, the shopfront was set back from the street and up two steps the width of the building, while the entrance to the floors above was to one side and read more like a fire exit than entrance.

In order to give the ground floor gallery a significant presence on the street we decided to co-opt the whole building façade in the service of our project. Where the shopfront had been recessed it was now brought flush with the street; where the brick-clad piers narrowed, they were now widened to create a strong base; in contrast to the poor post-war stock bricks we clad the columns in grey clay engineering bricks. Through these modest measures the ground floor gallery was given pride of place in the building, and the building gained in stature on the street.

Principle of Balance

In July 2008 we were invited to participate in the Kings Cross Charrette, a one day urban design workshop. The brief was to prepare a ‘mini-masterplan’ for an area behind the Kings Cross Central development currently being realised by developer Argent.

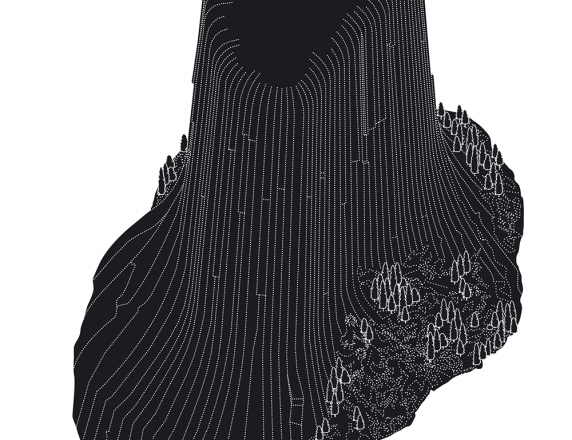

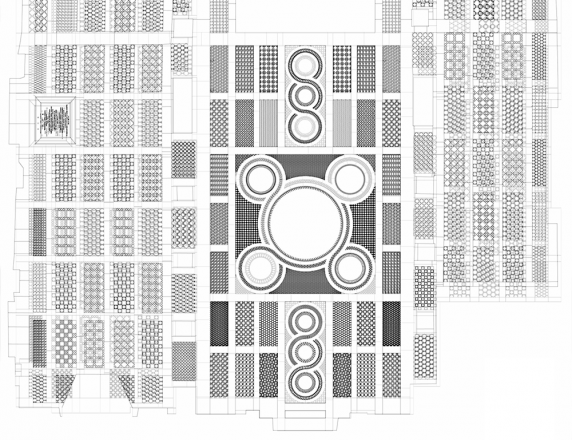

We read the site as a disparate array of urban fragments, social housing, warehouses, car-breakers yards, each brought about by different marginal economies over decades. In order to bring the area into greater and more pleasurable use it would first need to be more readily legible as a piece of the city. Our response therefore was to identify those fragments that gave the area its clearest sense of character and then to pair them up: open ground either side of the canal, tree-lined avenues to the north and south of the site, doubling the density of light industrial uses at the centre of the site. Pairing, mirroring and dividing are processes that make both parts and wholes legible simultaneously and could therefore exponentially increase the relationship between urbanites and their surroundings bringing about a coherence and balance the area sorely needed.

These principles underlie a desire to find continuity in the city by layering, extending, reconfiguring what is already there. The city worked upon by a jujitsu urbanist remains legible even while it changes so that the possibility of multiple interpretations and contradictions can grow exponentially.