Published in San Rocco, Issue 8, February 2014

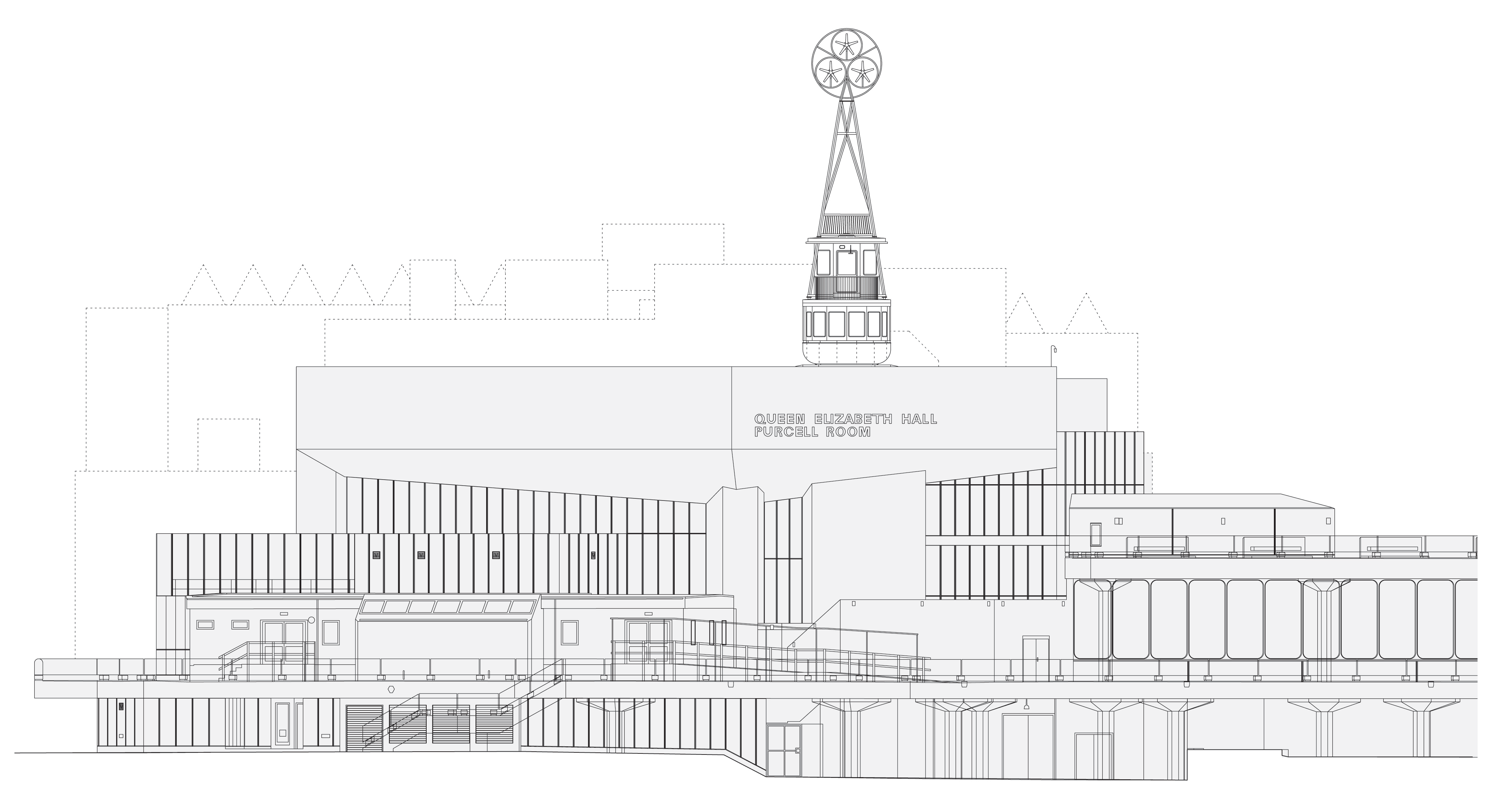

In 2010, a competition brief was published inviting architects to submit designs for “A Room for London.” The Room would be a temporary structure installed on the roof of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, part of the Southbank Centre, throughout the 2012 Olympic year. Two guests at a time would enjoy the “stunning views” of central London while artists and writers would be given residencies to produce new work. The competition organizers, Living Architecture and Artangel, wrote:

We envisage the Room as a space for quiet reflection and contemplation in the midst of the frenetic noise and urban activity all around it. The Room will offer a place of temporary withdrawal, a retreat from which guests can reflect on the problems and possibilities of urban 21st century life. It is a place from which one can look out at London – and in turn a place which Londoners can look at and wonder about.1

Even from the brief’s short descriptions of the Room and the city, certain assumptions about their characteristics, functions and relationship can be drawn out. The first is that the Room and the city are distinct and in some ways opposites: the city is a “frenetic”, noisy place of action, while the Room is a quiet space of “contemplation”. The Room is not inside the city but removed and unaffected by its presence. The second is that contemporary urban life is a condition unfettered by historical contingency that has essential qualities that can be observed, allowing its problems and possibilities to be deduced. This might be seen in contrast to an understanding of the city as constructed over centuries and as being subject to structural problems inextricably linked to its complex history. The third is that retreat from the city into the Room will provide the necessary conditions for the project’s the city’s objective understanding and critique.

The brief’s assumptions reinforce certain myths in various stages of production: the myth of London as a role-model 21st-century global city, of particular relevance during the Olympic year; the map-maker’s myth that a city can be understood from a privileged vantage point; and the myth of the philosopher’s study being a privileged space so removed from the contingencies of the world as to render its truths visible to the enquiring mind. Ultimately, these observations lead one to consider the myth of the origin of modern architecture itself, how it makes the claim to be able to create from scratch a site in which we might establish an entirely rational world that addresses the problems of the city through the realization of a perfected version.

As with all myths, there is much that they serve to hide from view. As Roland Barthes notes in his Mythologies, what the world supplies to myth is an historical reality, defined, even if this goes back quite a while, by the way in which men have produced and used it; and what myth gives in return is a natural image of reality. . . . A conjuring trick has taken place; it has turned reality inside out, it has emptied it of history and it has filled it with nature, it has removed from things their human meaning so as to make them signify a human insignificance. The function of myth is to empty reality: it is, literally, a ceaseless flowing out, a haemorrhage, or perhaps an evaporation, in short a perceptible absence.2

One myth of architecture’s origin is Marc-Antoine Laugier’s idea of the primitive hut, as described in his Essai sur l’architecture (1753). In his search for architecture’s myth of origin, Laugier returns to the idea of Adam building his house in paradise. Through a need for shelter from the sun and rain, dissatisfaction with the meagrecomfort afforded by woods and caves, man builds himself a hut. He uses what is immediately to hand – sticks, twigs and leaves – and constructs it in an entirely rational, efficient manner, starting with a structure that is clad in a weathering skin. To give this idea some historical context, in 1753 London had a population of 700,000 and was the centre of the First British Empire. The city was in the throws of the early industrial revolution, crime was rife, public hangings were commonplace and the skyline was populated by church spires, as depicted by Canaletto.3

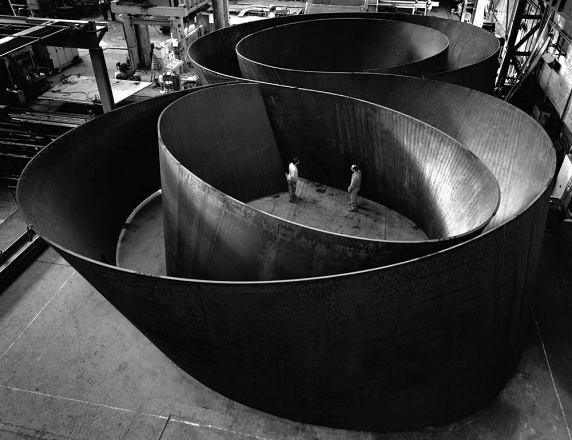

By 1920, the myth of modern architecture’s origin was updated through the adoption of the steamboat as its signifier. Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture heralded the ocean-going liner as evidence of a yet greater rationality, emblematic of societal progress. These floating cities literally detached themselves from early-20th-century European capitals and drifted into the sunset, transporting their passengers to the next plateau of modernity. Here the primitive hut’s sheltered patch of ground becomes a floating space, seemingly freed from boundaries and jurisdictions. Twigs and leaves are replaced by seamless, white surfaces that cleave silently through space. Although the construction and the signifier have been updated and streamlined, the ideology underlying the myth has changed little. Both the city and the architecture remain de-politicized spaces; the complexity and contradictions of the human acts that construct them are suppressed in favour of a more acceptable absence.

If one wanted to further problematize the myth of modern architecture’s origin, one need look no further than the detailed history of a steamboat of the same period. Perhaps the most provocative example would be the boat piloted by Marlow up the River Congo, a fictional journey richly described by Joseph Conrad in his 1899 novella Heart of Darkness. The story begins in London, on a yawl moored at Gravesend. A sailor recounts to others gathered on the deck the story of Marlow’s journey from London to the Congo in search of a shadowy ivory trader named Kurtz. Marlow eventually finds Kurtz and tries to bring him back to civilization, but Kurtz dies aboard the steamer during the journey.

Marlow travels aboard several craft on his journey south from Europe, finally arriving at a trading station on the Congo where he discovers a sunken steamboat at the bottom of the river. Once its metal hull is stitched together with rivets, he steps aboard to find that “she rang under my feet like an empty Huntley & Palmer biscuit-tin kicked along a gutter”.4 The steamer’s funnel projects through the hull’s roof, and in front of the funnel a small cabin built of light planks serves as a pilothouse. As Marlow and Kurtz begin their return journey to Europe, Marlow describes the steamboat as “this grimy fragment of another world, the forerunner of change, of conquest, of trade, of massacres, of blessings. I looked ahead – piloting. ‘Close the shutter,’ said Kurtz suddenly one day; ‘I can’t bear to look at this.’”5 Conrad’s Heart of Darkness adds to the steamboat’s narrative of technological progress its role as a vehicle of European cultural imperialism.

“A Room for London” therefore seemed to provide an opportunity to decipher one myth about architecture’s origin and reveal its inherent distortion of history. The artist Fiona Banner and my studio collaborated on a submission for the competition that consisted of all the excerpts of text from Heart of Darkness referring to the steamer and drawings of a boat being lifted onto the roof of the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Its fragile timber-and-metal form was to be in stark contrast to the vast swells of concrete that characterize the arts centre. It was to be cantilevered over the edge of a bluff, as though only temporarily come to rest. Rather than this being an escape vessel in which to remove oneself from the city, we designed it to be a craft returning from a voyage, full of memories and traces of history. Rather than a smooth architecture of absence, we wanted this to be a splinter in the present, bringing back into sharp relief all of those stories and people that the myth of architecture’s origin has managed to suppress.

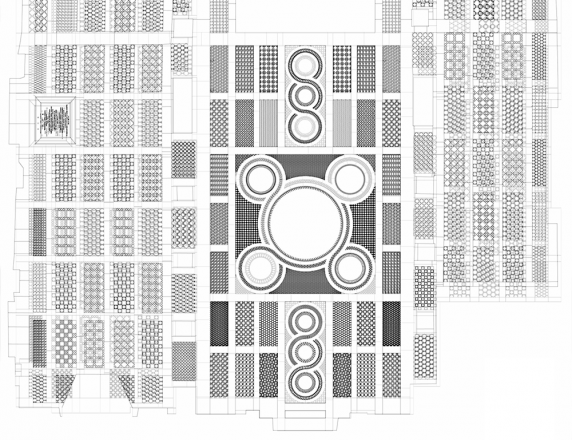

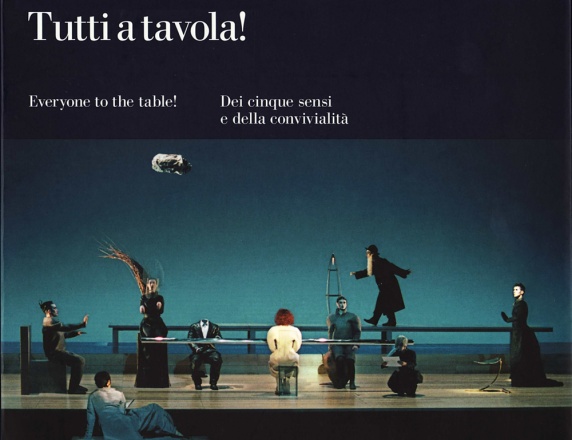

We called the boat the Roi des Belges and modelled it on the one photograph that survives of Conrad’s 1889 charge as well as on the fragments of text we had excerpted from the novella. We wove these details into a design that also made reference to the interiors of Sir John Soane’s Museum and the church spires of Hawksmoor. The interior of the metal hull is lined in red-stained plywood with Bakelite fixtures and fittings. The octagonal pilothouse, lined in blue-stained plywood and accessed via a drop-down ladder, contains a library of all the works of Conrad, books about the history of colonialization and literature of the African diaspora. The view from the room within the hull extends from Big Ben in the West to St. Paul’s in the East. A cabinet positioned by the window facing the city of London opens to reveal a drawing by Gandy of Soane’s designs for the Bank of England in ruins, alongside maps of the Thames and Congo rivers and a glossary of nautical terms. On an adjacent octagonal card table sits the logbook of the Roi des Belges, with space for an entry for each hour of each day where sailors are asked to note their location and course, and details about the tide, water surface, clouds and wind.

Compared to modern architecture’s dream of city-scaled ocean-going liners, the Roi des Belges is an awkward, uncanny vehicle. It is comfortable insofar as it supports your daily life aboard, but it is otherwise seeking to make you aware of the Thames as London’s link to the rest of the world, as well as to some of its own darker depths and uncomfortable truths. The broader project from the perspective of architectural discourse is to reclaim the steamboat’s form as a vehicle for the philosopher-pirate, one able to see the world in all its contradictions and inconsistencies, its open-endedness. This journey’s aim was to return from the horizon into which liners once disappeared, laden with stories of human significance. Now brimming with contingency, “A Room for London” might no longer be removed from the city, but rather be within it, and the city need no longer be emptied of history.

Notes

- Living Architecture and Artangel, A Room for London, available at http://www.living-architecture.co.uk/aroomforlondo..., 19 November 2011.

- Roland Barthes, Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 142–43.

- Canaletto, The River Thames with St. Paul’s Cathedral on Lord Mayor’s Day, ca. 1746, The Lobkowicz Collections, Prague Castle, Czech Republic

- Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (London: Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1995), 56.

- Ibid., 96.